Homebrew 6502 computer

[Back to the homebrew computers page]

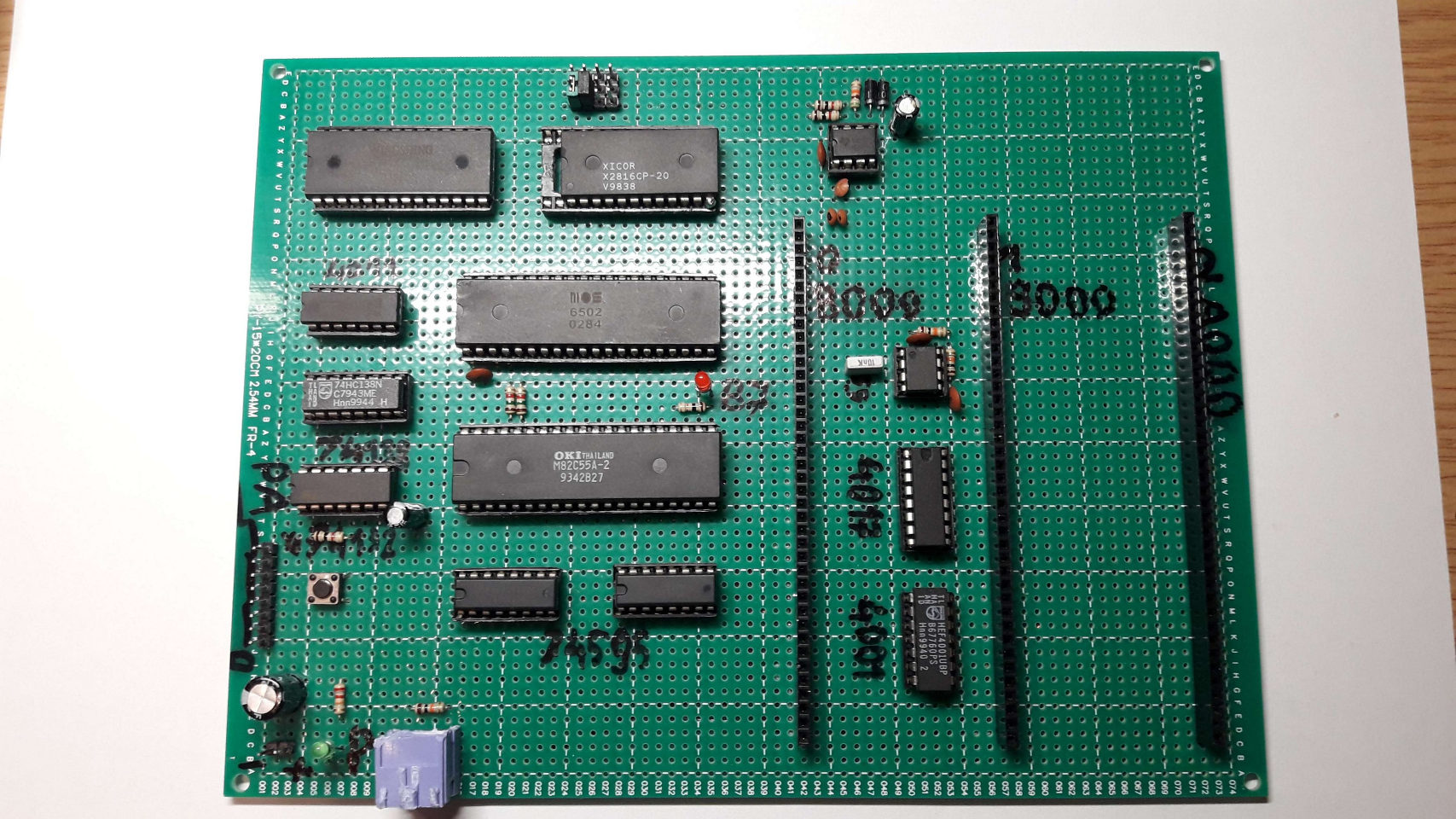

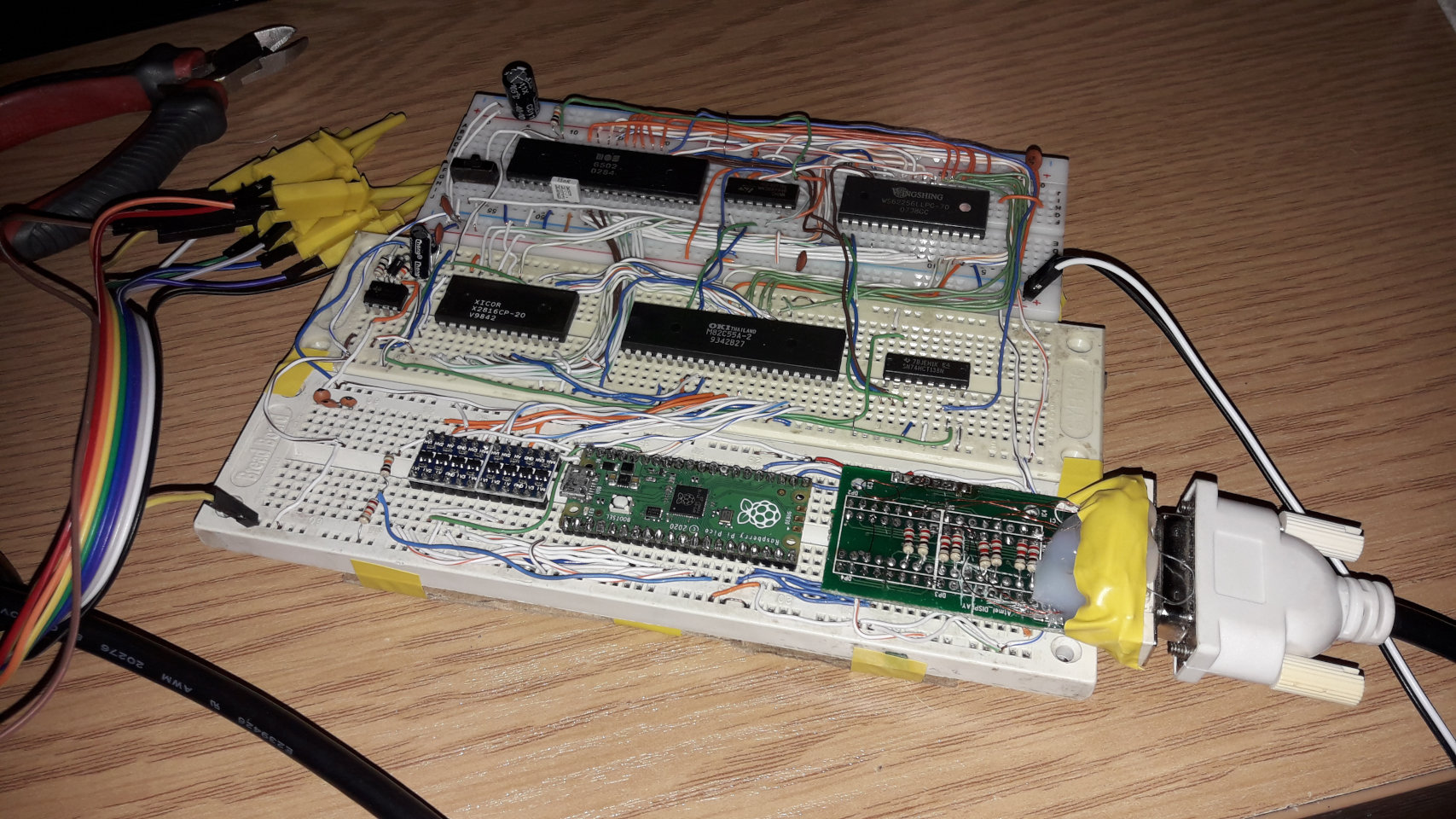

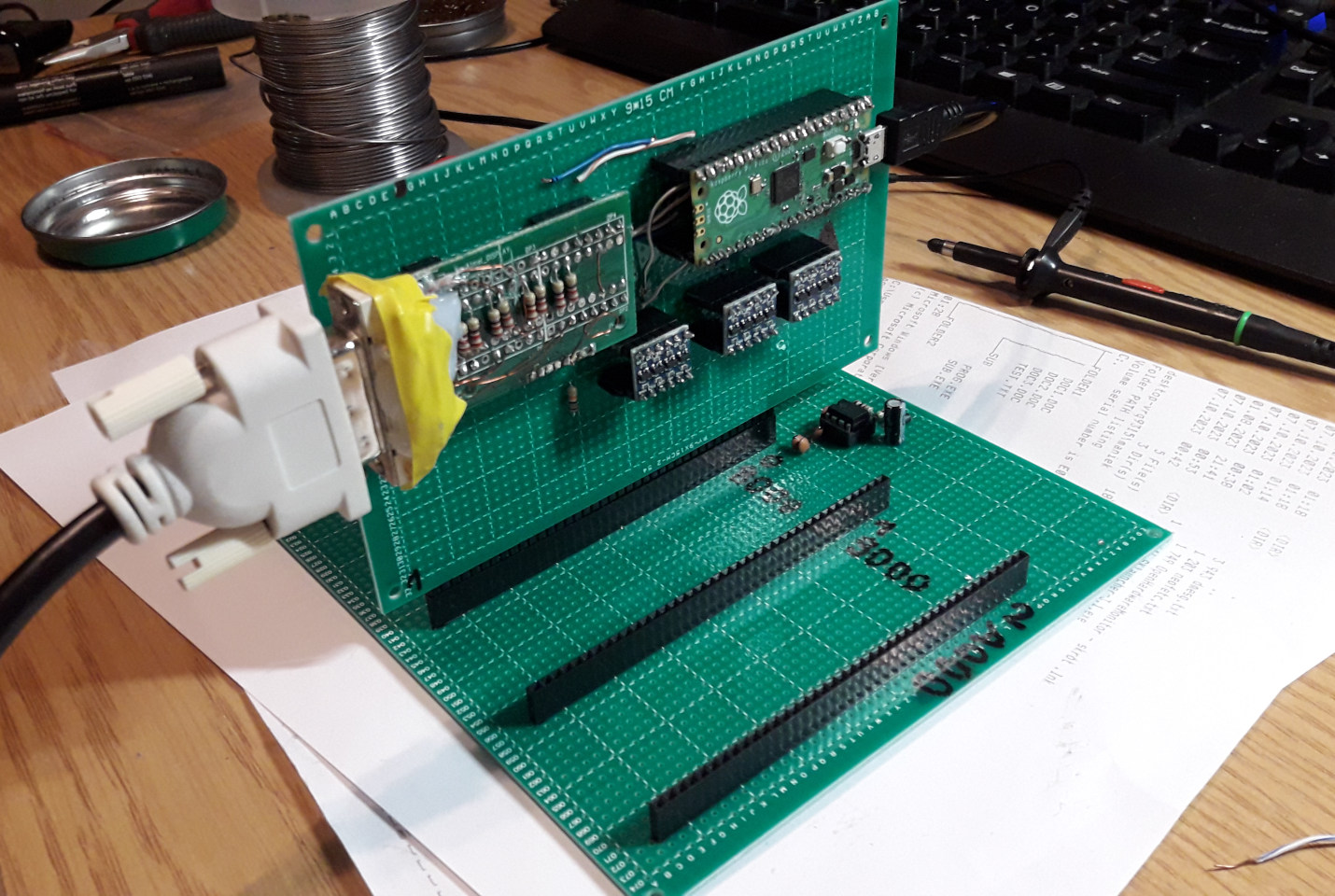

The finished result

Specs

- MOS 6502 running at around 1 MHz

- 32KB of SRAM (62256)

- 2KB / 16KB of ROM (2816 or 28256 used in half)

- Intel 8255 - 24 I/O lines

- Custom PS/2 keyboard controller

- Three expansion slots

Current state: Lying in my closet, with some of the socketed chips missing (borrowed for other purposes). I can tell that it was great learning platform!

Repository with various stuff made during development: https://github.com/maniekx86/homebrews_6502

Schematic: https://maniek86.xyz/pliki2/projekt_6502/prototype_pcb_6502_schematic.pdf

History

Continuing from the backstory...

I learned how the 6502 exactly works by working with the simulated model in Logisim, not by reading the datasheet. When I started working with the 6502, I didn't relook at Ben Eater's videos because I wanted to create something from scratch rather than use an existing design. As I mentioned in the backstory, I postponed the idea of making a 6502 SBC because I didn't have the necessary parts. However...

Parts gathering

I found a MOS 6502 from 1984 on a local auction site for very cheap. I bought it, but I still need many parts, such as logic ICs, RAM, ROM, and I/O. Everything changed in the summer of 2023 when I received an old, broken "multimedia" CRT TV from my dad. It was corroded inside because, it had been left outside for a long time. However, many of the electronics inside were fine. I decided to take it apart because even if I attempted to fix it, I wouldn't have a place for it, and I was less experienced than I am today. Why did I call it a "multimedia" CRT? It had many DIN connectors for a proprietary home multimedia system. I don't remember the company name. Thanks to that, I found an entire single-board computer inside, built on top of an Intel 8051 (to be more exact - Intel 8032) with SRAM, EEPROM, some logic ICs and even an 8255 I/O chip. No stupid all in one integrated proprietary chip - amazing! I decided to desolder this board.

Yay! I finally had all the parts I needed to build something meaningful. I thought I could use the 6502, a 62256 RAM chip (32 KB) that I gathered from an other desoldering session, as well as the ICs I gathered now: X2816C (2 KB EEPROM), 8255 (input/output IC), and a few logic chips to build my own 6502 computer. But wait! there's one thing I'm missing: how do I program an EEPROM without a programmer? At the time, I couldn't afford to buy a programmer. So, I decided to build one myself - a one specifically for the 2816 EEPROM.

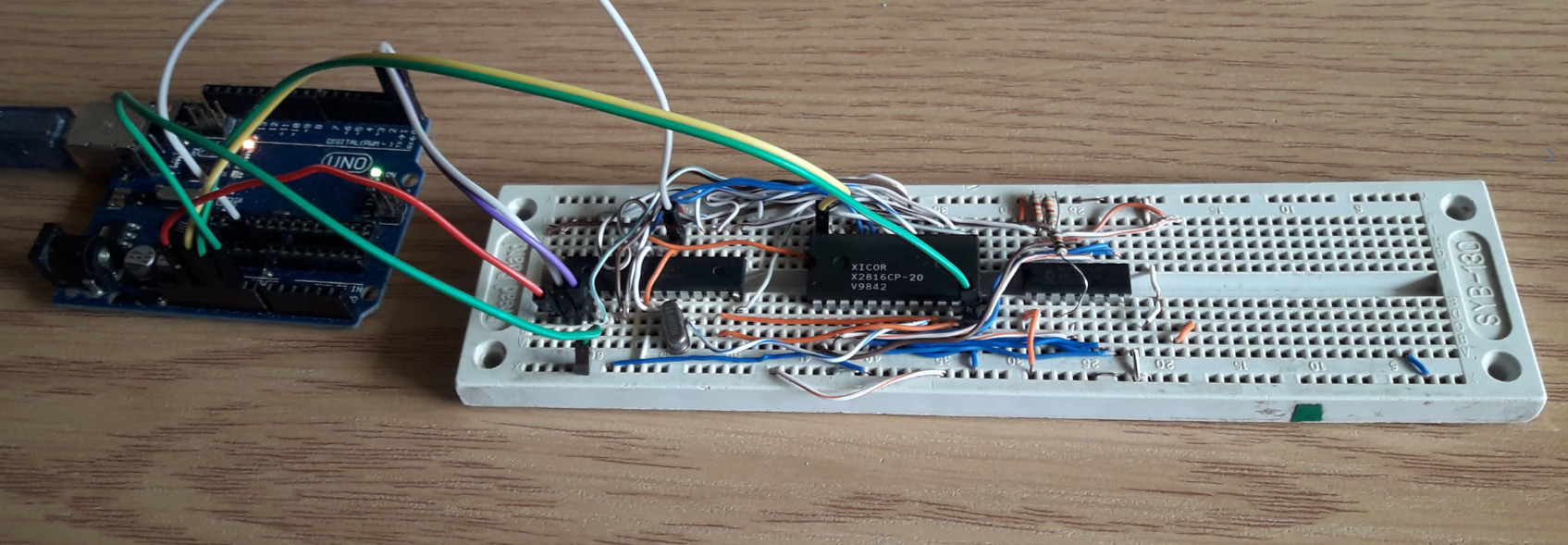

Building a programmer

I had an Arduino Uno available in my storage, so I decided to use it as the base for the programmer. However, the Arduino didn't have enough pins, so I had to use a PCF8574 pin expander. After some tinkering and coding, I got it to read and write EEPROMs. It worked well enough for my needs.

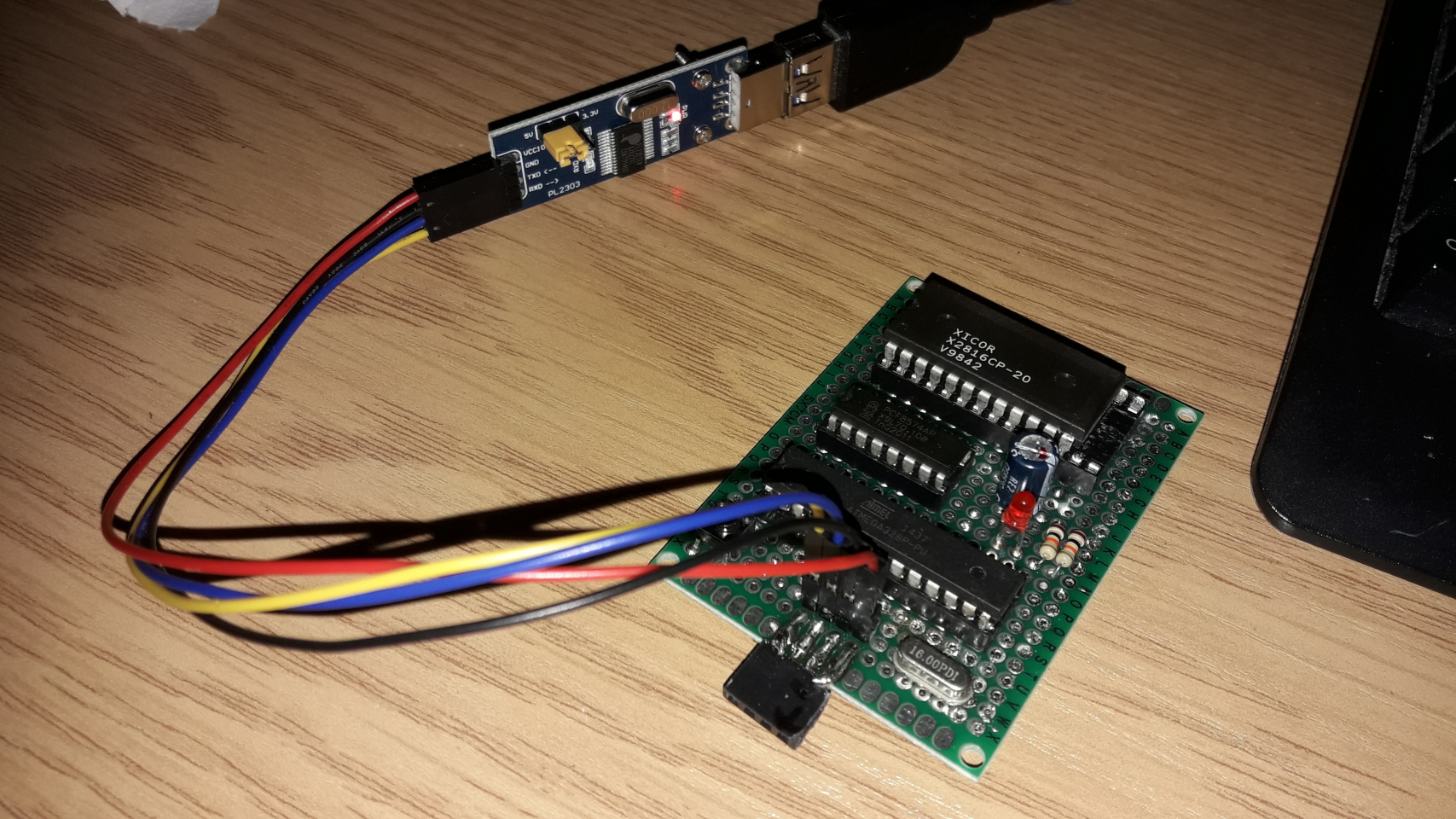

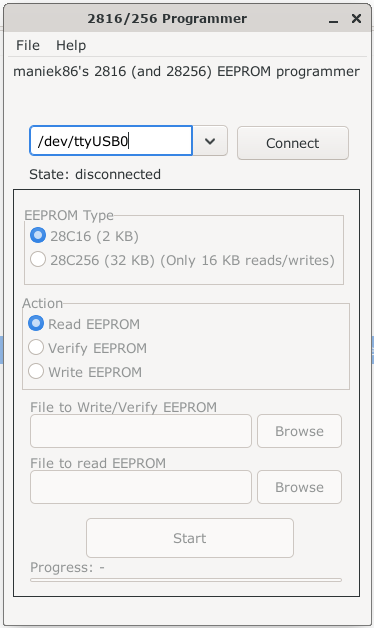

After creating a working prototype of the programmer on a breadboard, I decided to move it to a prototype PCB. I even wrote a small, nice GUI utility in C++ with CodeBlocks. Source codes are available on GitHub in the homebrews_6502 repository under "programmer" directory.

There is no schematic because I did not make one. I don't guarantee that it compiles and works today - it was just my cheap way to program EEPROM.

It was so cheap that I had to use a larger socket for the IC - I had a few DIP-28 sockets but no DIP-24 sockets. So, I used one. Anyway, later on in the development process, I updated the programmer to also support 28256 EEPROMs, which come in DIP-28 sockets, so this decision ended up being useful. To interface it with a PC, I used a USB to UART converter

You might be wondering why the 28C256 option says "Only 16KB read/writes". That's because I ran out of I/O pins. I had two PCF8574 I/O expanders, as seen in the breadboard photo above, but I fried one when I accidentally plugged it in backwards. As you may have noticed, I had a really low budget for building this homebrew, so I was left with one expander. This wasn't an issue for the 2816 EEPROM because the number of pins on the ATMega with one expander was enough. I even had one IO pin left over to add a status LED! However, this became a problem when I wanted to modify this programmer to support the larger 28256. I was missing one pin! I even removed the status LED (I had connected it to power only, to indicate power instead of blinking during activity). So, I was left with a programmer that could address only 16 KB. I came up with a solution: adding a switch connected to the last address line. Based on its position, I can now address either the lower or upper 16 KB of the 32 KB EEPROM.

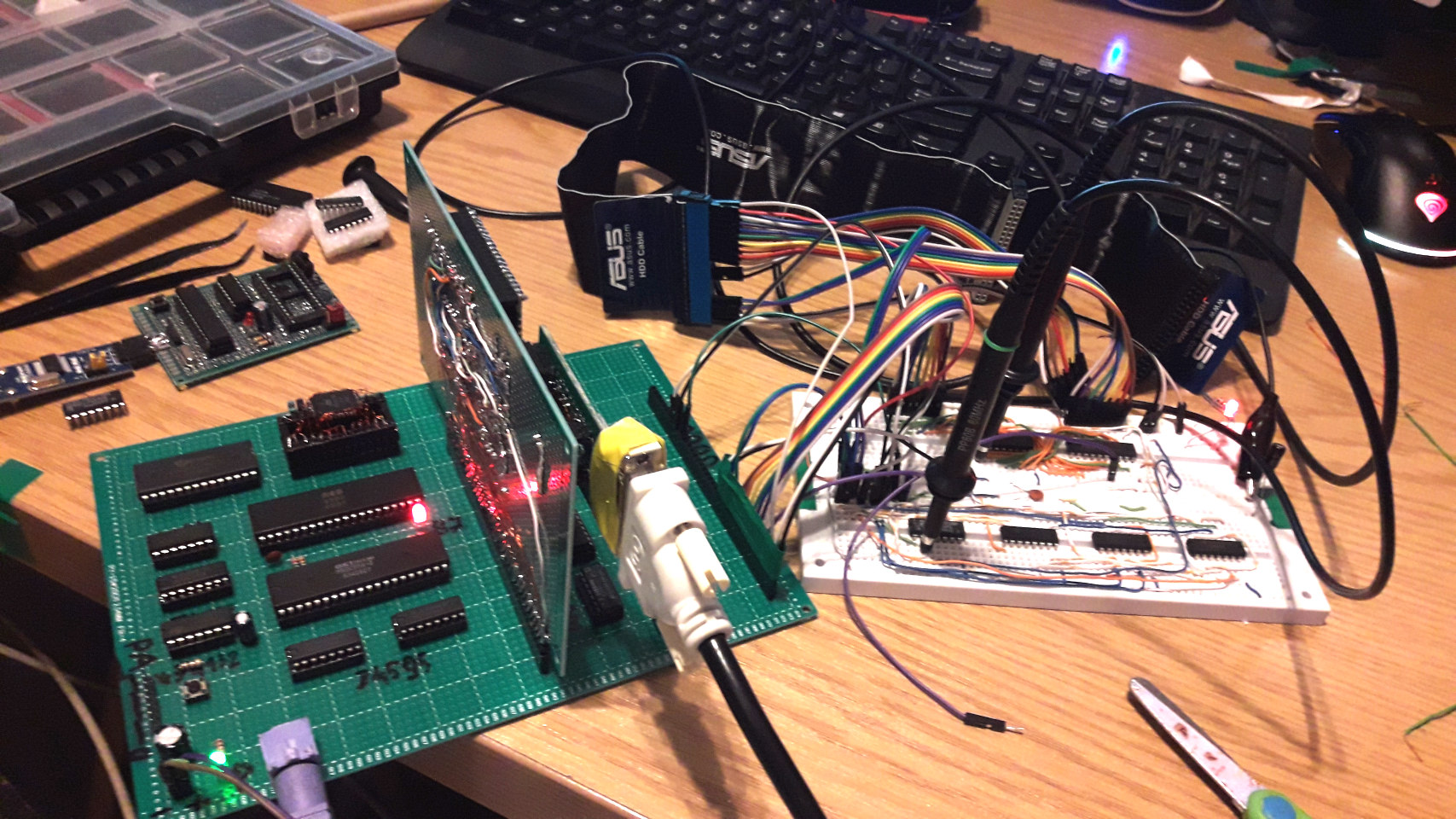

Homebrew computer on a breadboard

After finding a way to program any EEPROM, I could finally start working on the project. One thing about this project is that I did not make a schematic for it. I worked on it "with the flow", meaning I connected the address lines to the address lines and the data lines to the data lines, leaving the control lines for the end.

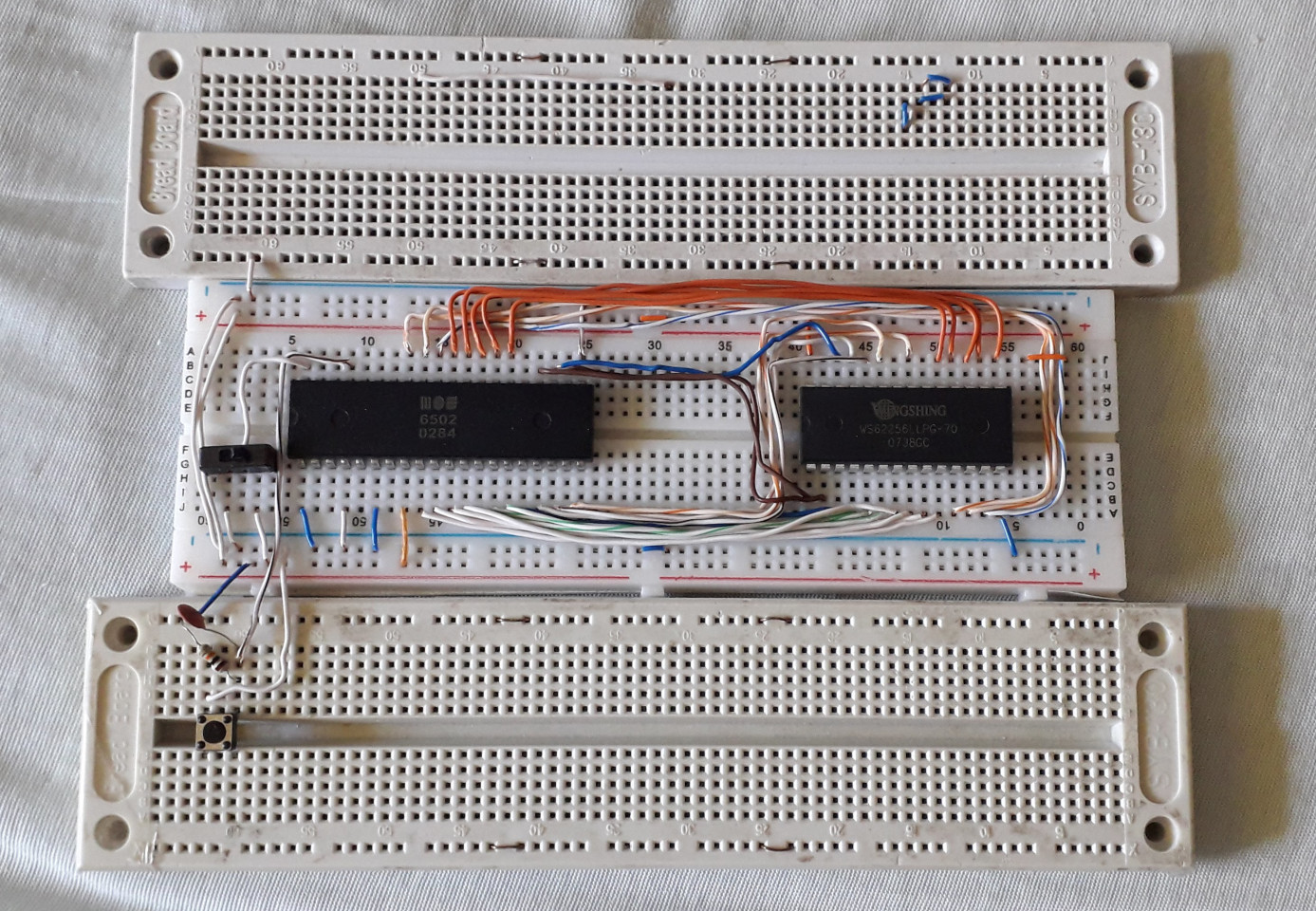

The 6502 is on the left and the 62256 is on the right. The CPU is clocked by a push button, and reset is handled by a switch.

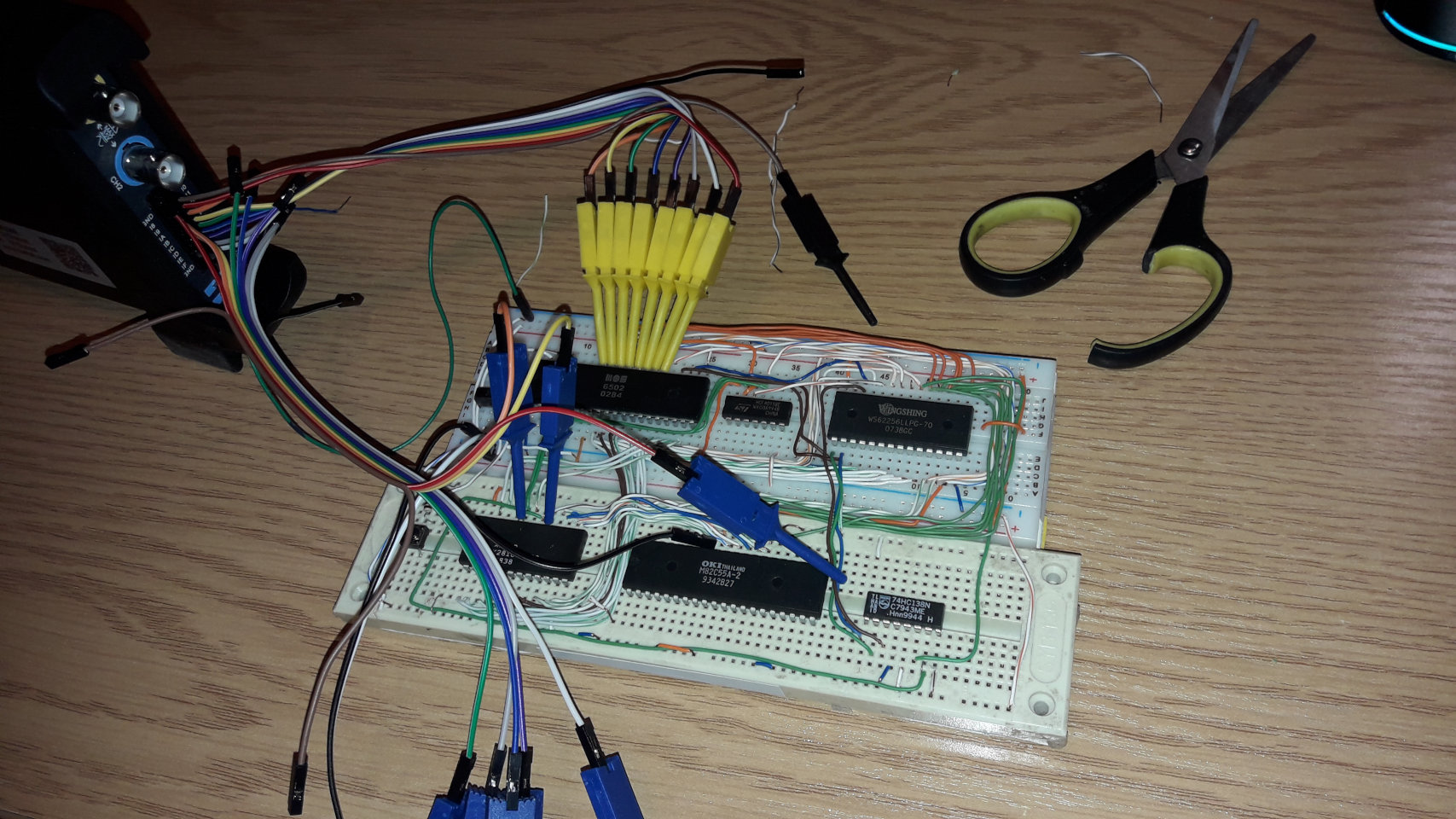

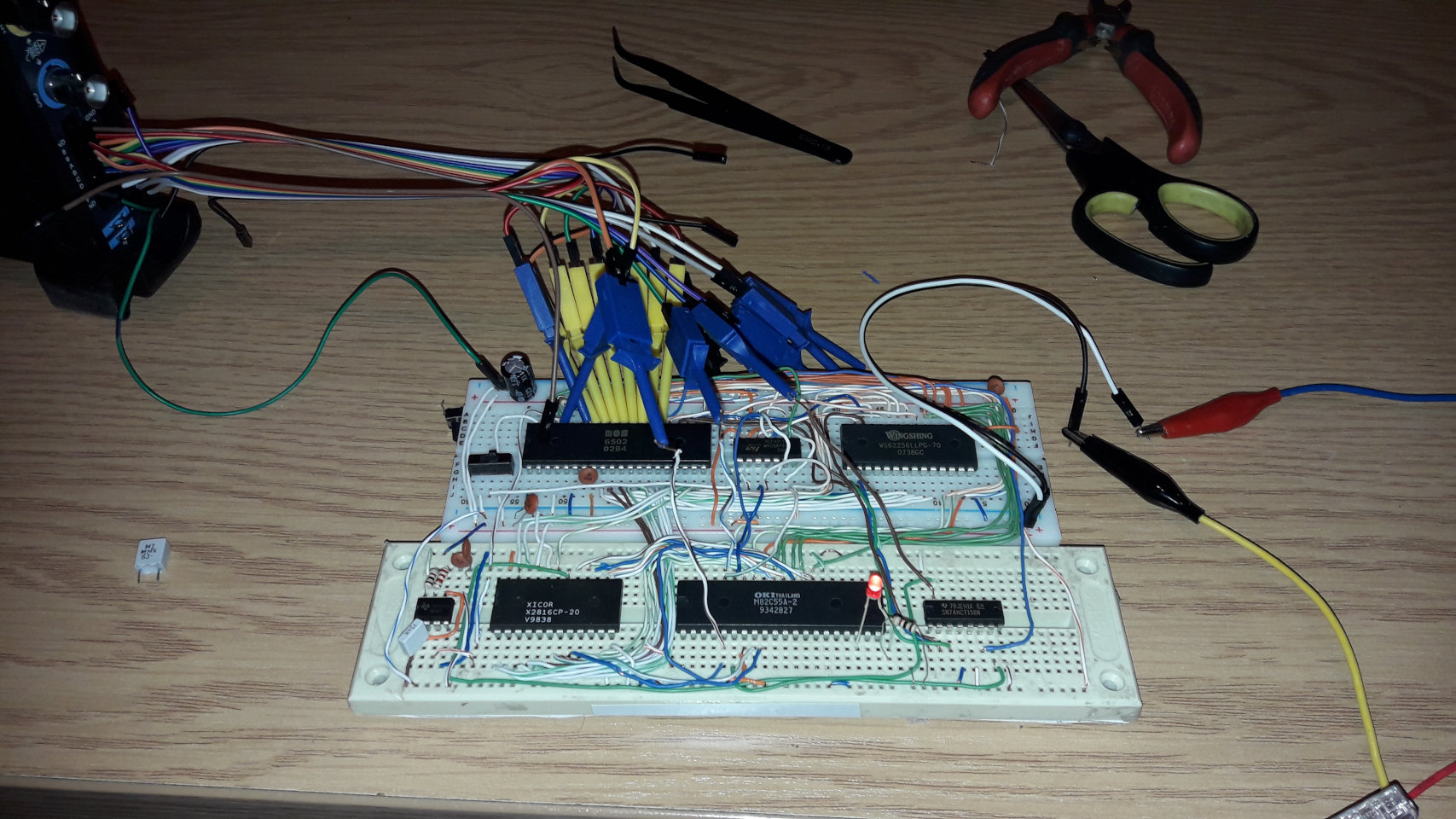

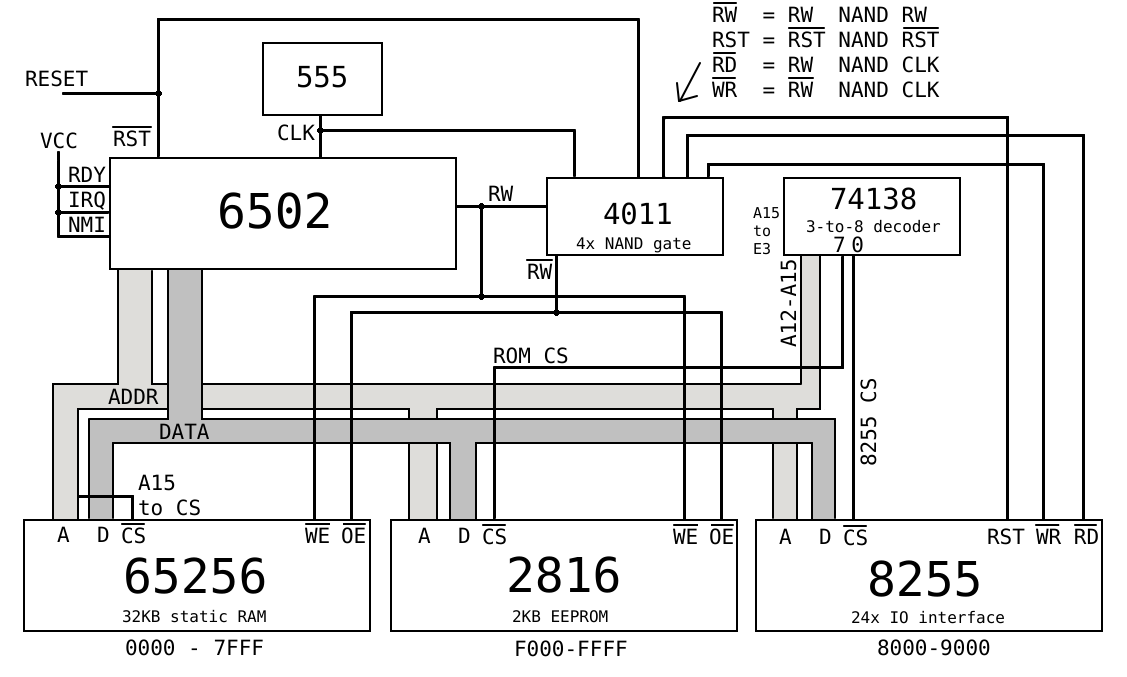

I removed the top breadboard and added a CD4011 NAND gate, a 2816 EEPROM, an 8255 input/output (I/O) chip, and a 74138 decoder. I used the 4001 NAND gate to generate the Intel WR and RD signals for the 8255 IC. At the time, I actually had a cheap Hantek 6022BL oscilloscope with a 16-channel logic analyser. I used it to debug my build. For a simple 6502 running at less than 1 MHz, it captured the data pretty well. For the oscilloscope part, I used OpenHantek and for the logic analyzer part, I used PulseView (I used and I am still using Linux). I was happy to see any activity on the CPU from the logic analyzer! I remember that at the start, I wrote a simple JMP $ (infinite loop) program for the tests. After this, I added an LED connected to the 8255 and wrote a simple program to just light up the LED connected to the IO chip and the results were good too!

I proceeded to play with it like a microcontroller. I got the LED to blink and then got the CC65 C compiler to work on it. After all, I had plenty of RAM (32 KB). The second thing I wanted to do was drive a display. I wanted to use a classic HD44780 16x2 alphanumeric display, but I didn't have one available at the time. However, I did have an ST7920 128x64 graphics display. Having C available made driving it easier. In few hours I managed to get the screen to display the classic "Hello World!". Having a computer on a breadboard was a truly wonderful experience for me.

Yes, it was that slow. As I recall, the CPU was running at 200 kHz (still clocked from the 555).

Below I drew simplified architecture of what was currently made on the breadboard.

Going further on breadboard

I wanted to make this homebrew do more, like have keyboard input and an actual display output. At that time, I was not as experienced as I am today, so I came up with a lame way of using a microcontroller for video. I had a Raspberry Pi Pico and a very DIY DVI breakout board (made from the front display PCB of an old satellite receiver, hehe). I could plug it into the breadboard, connect it to the RPi Pico, and have a DVI output. I used the PicoDVI library, which offered many graphics options. In the end, I decided to use an 80x60, 1-color text mode running at 640x480 pixels. I designed an interface for the CPU using an I/O chip as a passthrough. It was slow, but easy to implement with the Pico (slow I/O on the CPU side meant that I could use a simple I/O reading loop rather than dealing with complex PIO stuff). Also, the Pico is 3.3V while the rest of the circuit is 5V, so I had to use level shifters. I also experimented with the clock circuit and by adding a diode I got it to clock higher (but still under 1MHz).

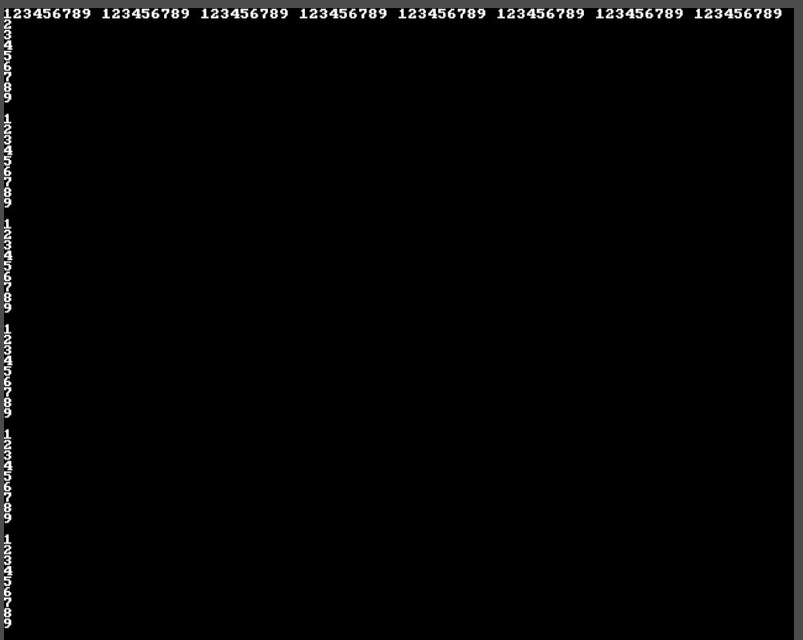

Pico 80x60 DVI output

There were no address lines connected, only data lines and two control lines. One was a data strobe and the other was a register selection. There were two registers: a command register and a data register. I implemented a basic set of functions to set the cursor position and write ASCII data on the screen. It was simple, but worked well.

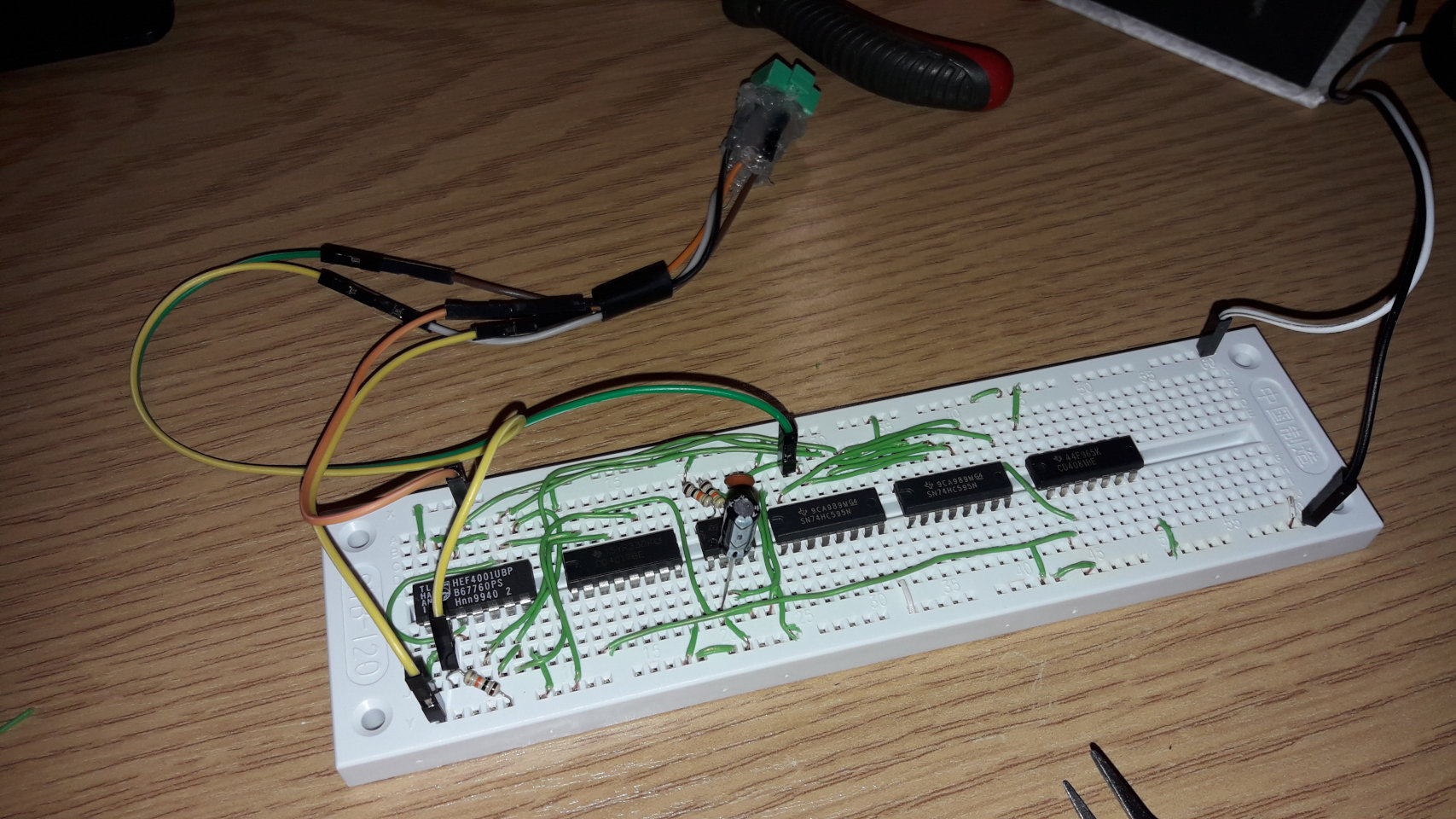

The next thing I wanted to add was a keyboard controller. I went with the classic PS/2 interface. Initially, I did some testing by connecting it to the Raspberry Pi Pico, but I thought it was lame. I bought two 74595 shift registers and started experimenting with building a basic PS/2 keyboard controller.

Through experimentation, I managed to create a simple 8-bit microcomputer-friendly keyboard controller. I used a CD4001 NOR, a CD4011 NAND (I used only one gate of the 4-gate NAND for interrupt), a 555, a CD4017, and two 74595 shift registers. It works by using the timer 555 and the CD4017 as a timeout detection circuit. The CD4017 is clocked by the timer 555. When the CD4017 reaches 9, the shift registers reset. To prevent this, the CLK signal from the PS/2 is connected to the reset pin of the CD4017, so when a bit arrives, the counter resets. To detect the end of transmission, the last bit (the stop bit) must be set to 1 because its output is connected to the NAND gate and the second pin of the CD4017. When the end of transmission is achieved and the counter hits 2, the NAND gate goes low, which generates an NMI interrupt to the CPU. The CPU fetches data from the controller through the shift register outputs (data bit lines), which are connected to the 8255 I/O chip. The schematic is available on page 8 of the entire homebrew schematic.

PS/2 controller. At this time, I had to use a crude DIY PS/2 connector as well.

I easily embedded the PS/2 keyboard. Why did I use NMI for the keyboard interrupts? - For some reason that I don't really remember, it was easier for me to get NMI interrupts working than normal IRQ. But honestly, that's fine for a simple homebrew project created by a beginner. I programmed the NMI routine in 6502 assembly while keeping the main program in C.

The IRQ handler was responsible for converting PS/2 scan codes to ASCII characters and placing typed keys in a circular buffer. It also tracked the status of special keys, such as shift, control, and alt.

In the end, I wrote a simple program that displayed the keys being typed on the screen.

After this success, I was happy. However, as other projects came along, I left the this project for about 1.5 month.

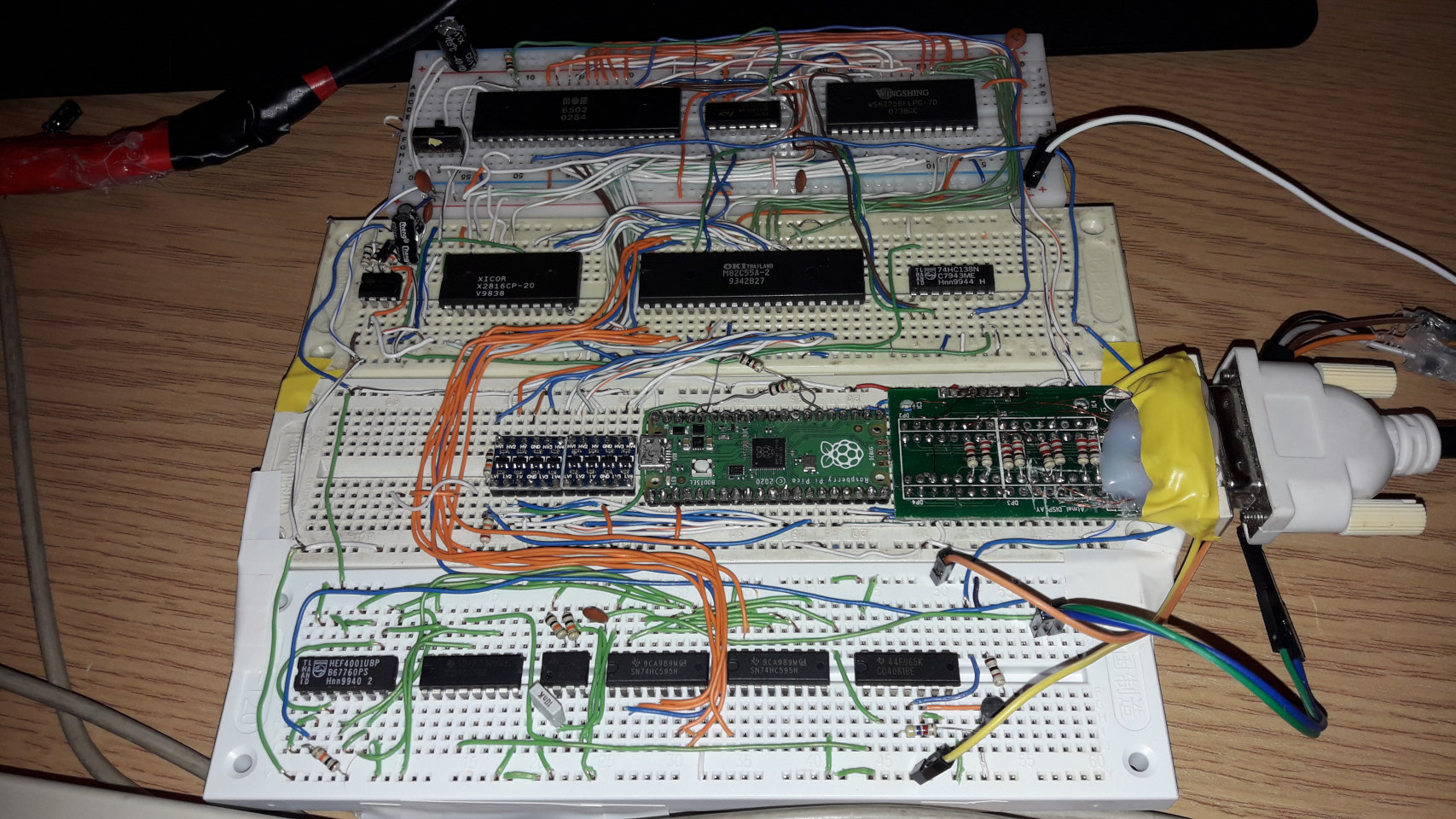

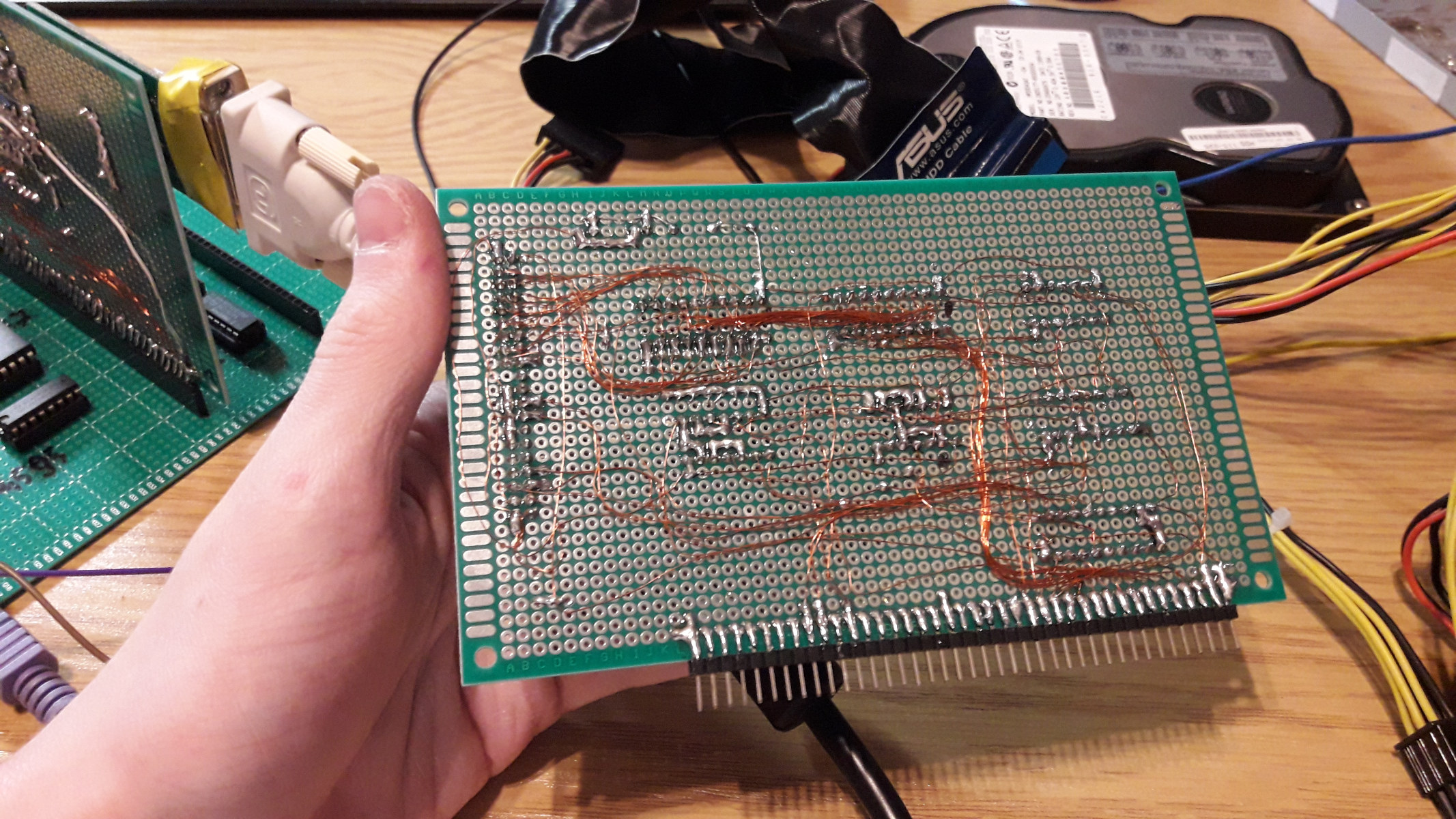

Prototype PCB version

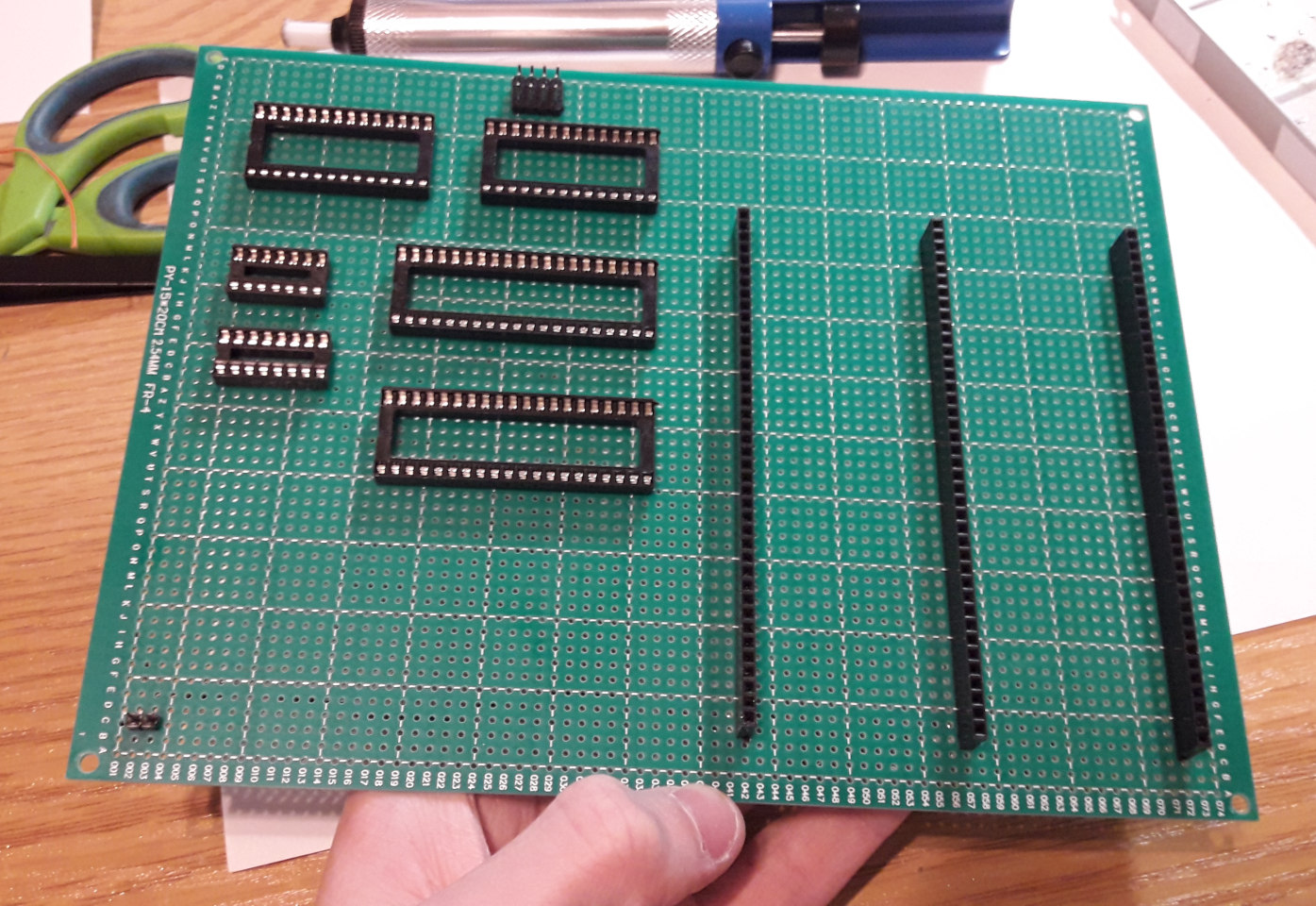

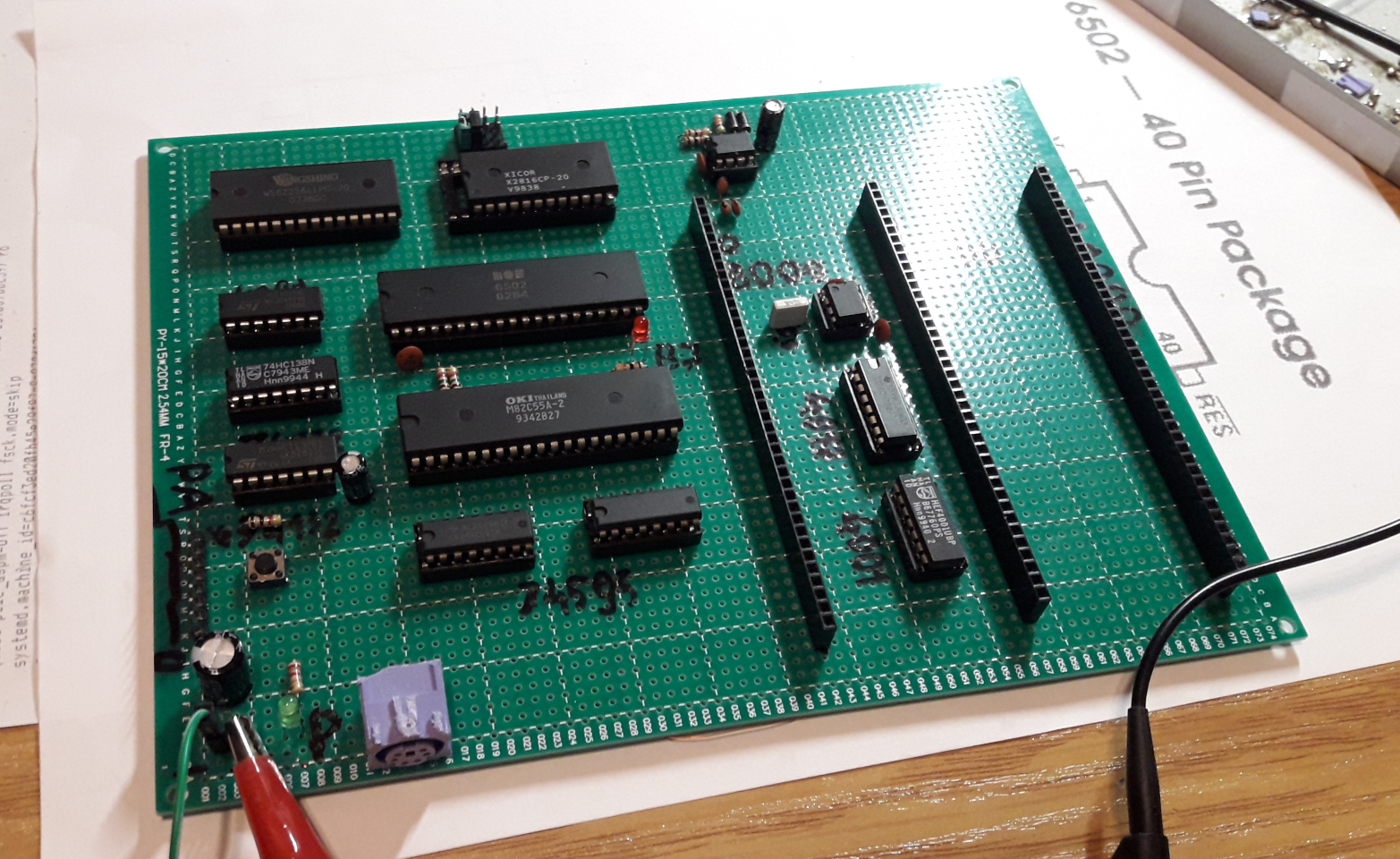

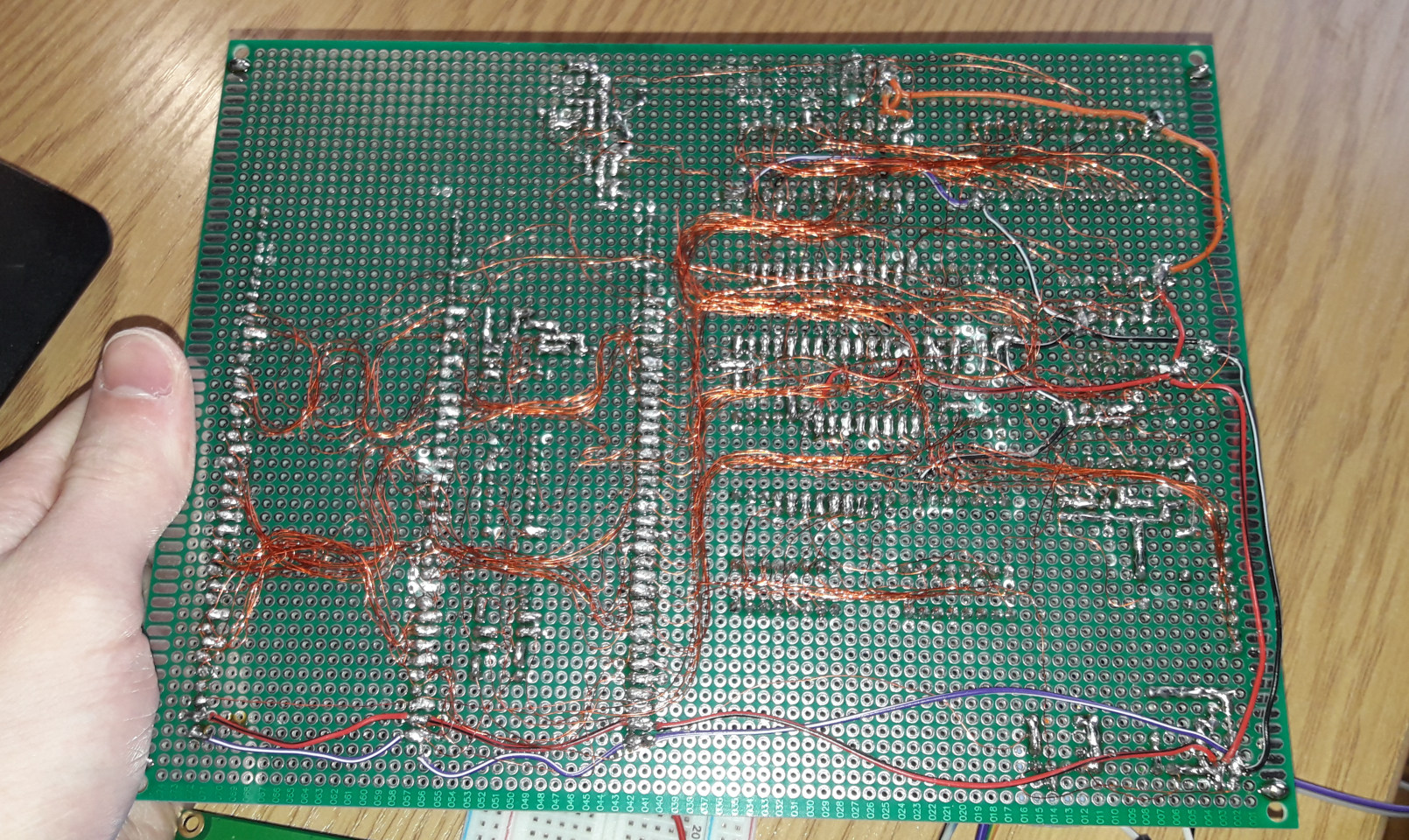

During my break from the project, I saved up some pocket money. I also had the idea to move the build from the breadboard to a more permanent and reliable setup. I decided to use a prototype PCB board. Why not make a PCB? PCB manufacturing was too expensive for me, and I lacked the necessary skills. So, I bought a 200*150mm prototype PCB, some sockets and gold pin headers. For connecting elements, I extracted thin enameled wire from the motor (which I still use to this day for projects like this and various repairs almost 2.5 years later!). I also bought three smaller boards to make expansion cards.

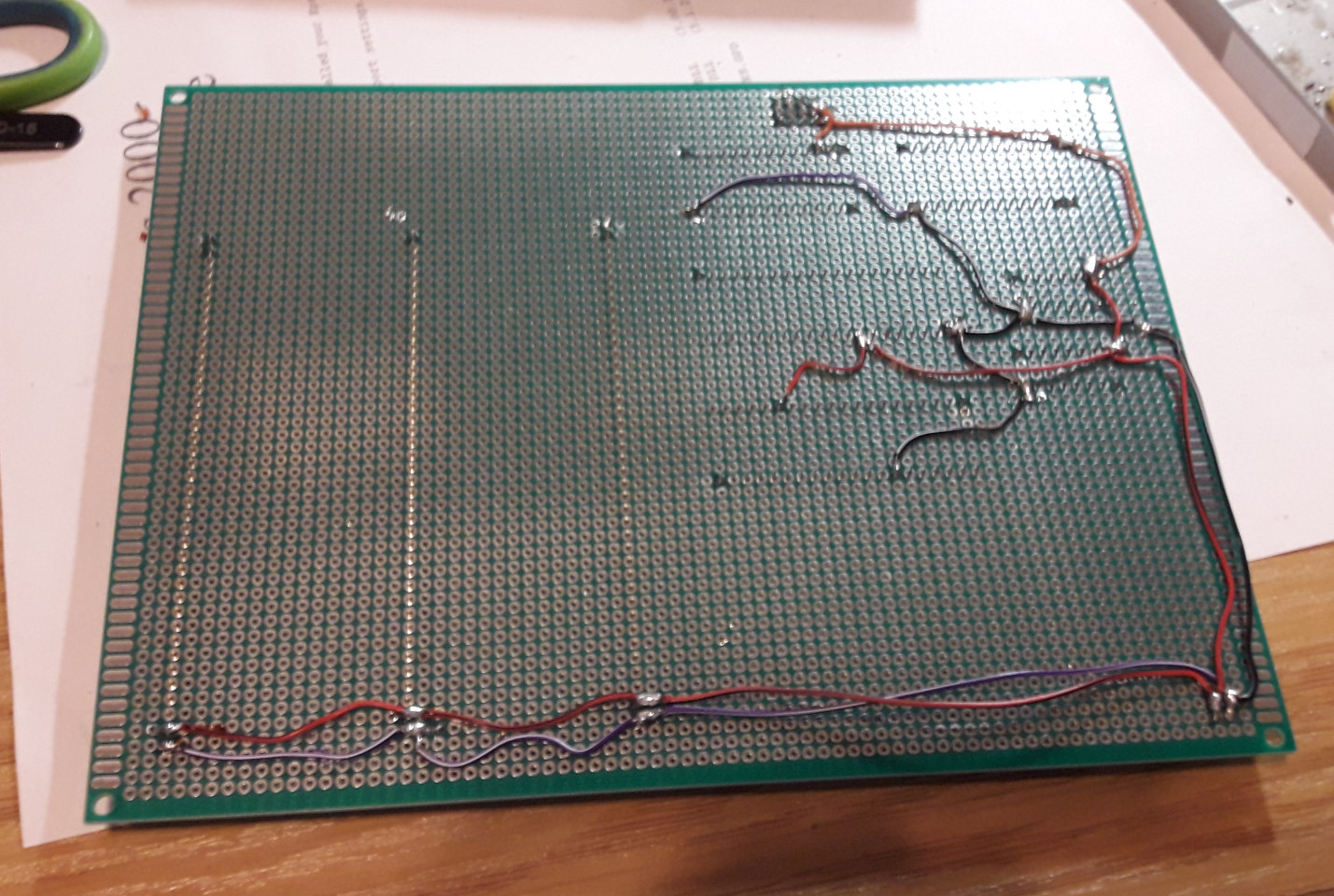

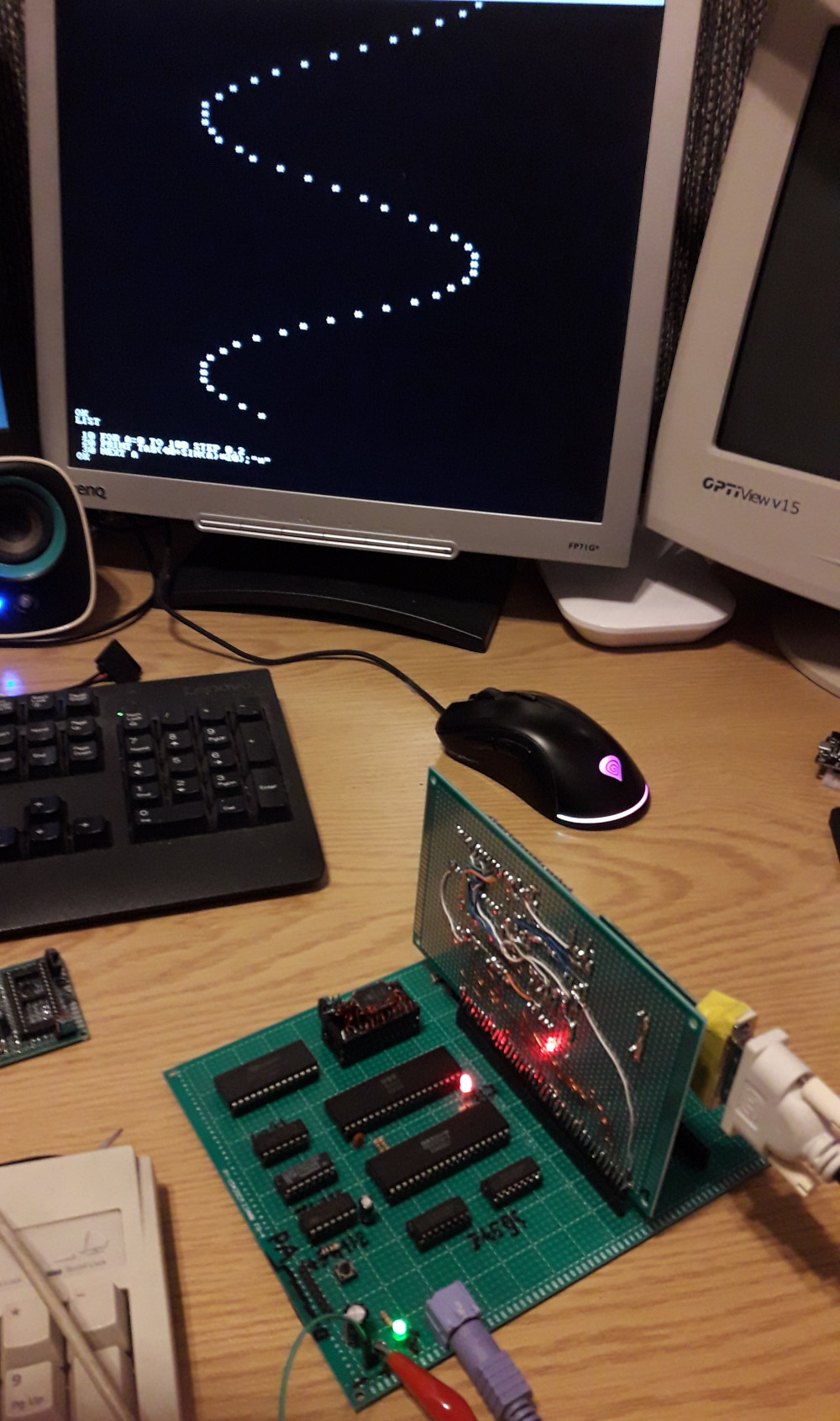

I began the soldering process. I arranged the elements in a way that I thought looked good and would not be too difficult to connect. I still went with my strategy of not making a schematic first. I placed three expansion slots. These exposed the entire 6502 bus, as well as a few extra signals, such as the 74138 decoder's free output signals. I used a bigger socket for the ROM because I forgot to order a socket for the 2816 EEPROM, but that came in handy later. I managed to get a 32 KB 28256 EEPROM, and by changing two jumpers, I could choose which EEPROM type to use. In like 2 days I got a simple blink running on this thing and few days later I finished the entire thing. I used the 555 timer again for the clock. The first blink was achieved in about two days.

After getting the base to work, I soldered on more components, such as the keyboard controller. I also experimented with the 555 timer to get 1 MHz out of it. I did this by adding two diodes between pins 7 and 6 (see the schematic). In the end, the whole thing worked flawlessly!

By the way, the larger 27C256 EEPROM I got, was in a PLCC package, however, using my soldering skills, a DIP socket and enameled wire, I adapted it to a DIP! You can see it in the pictures later in this article. There was also a third jumper for selecting the top or bottom 16 KB of the EEPROM, similar to the before mentioned switch on the programmer.

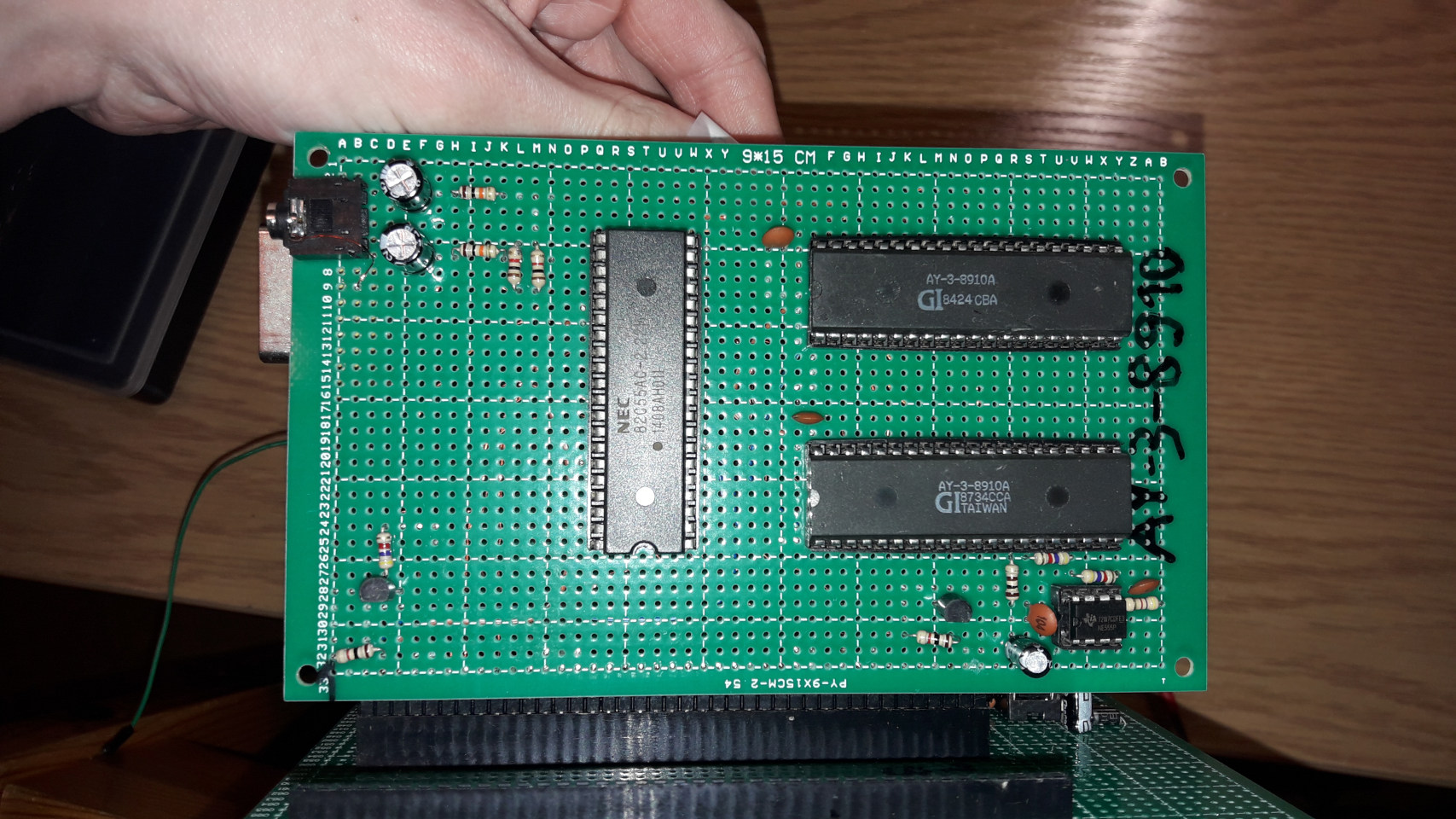

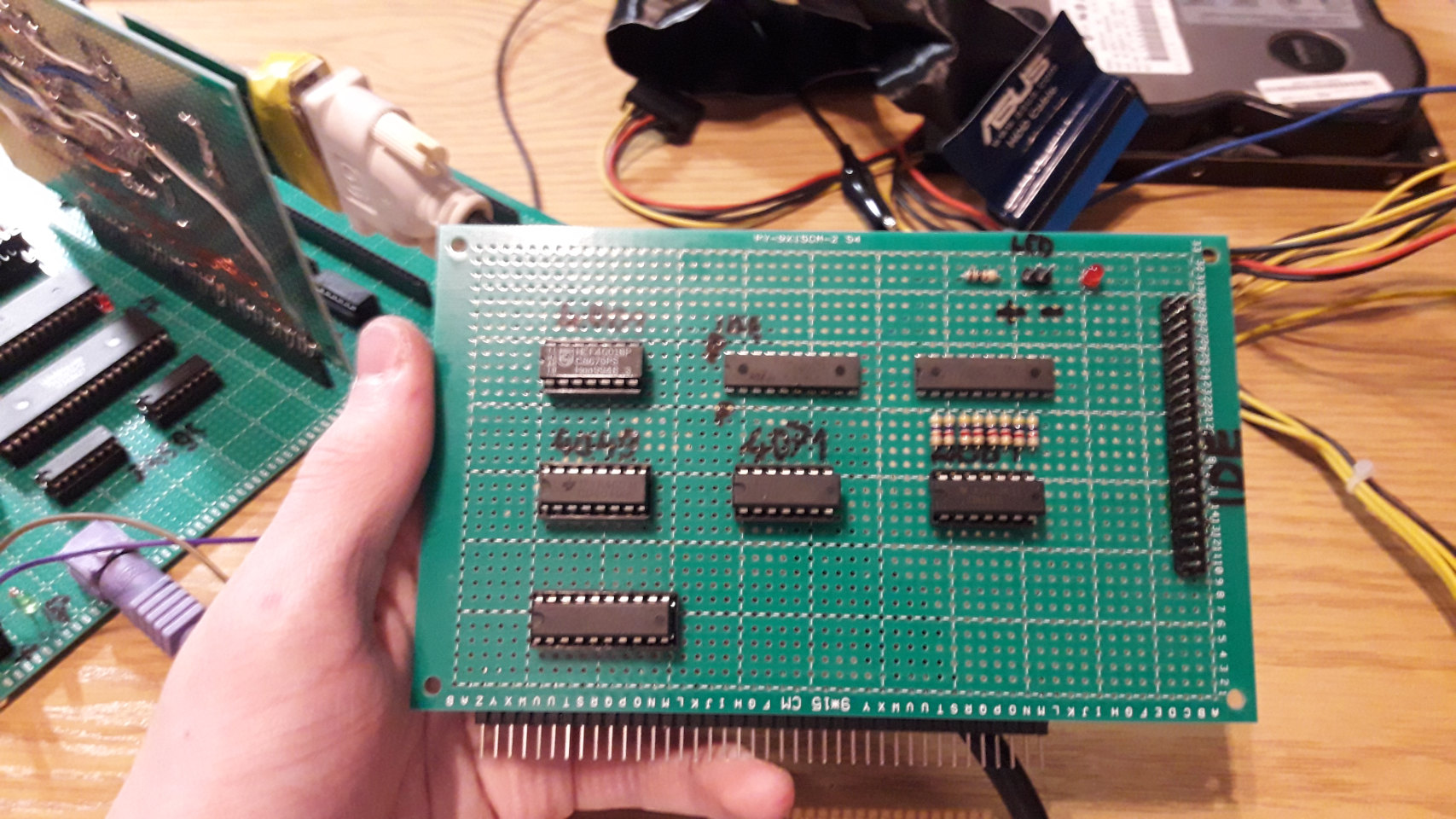

Expansion cards

I finished the base. In addition to the CPU, RAM, and ROM, it included three expansion ports, one I/O chip, and a keyboard controller. Of course, I wanted it to do more, like display something on the screen (like the previous version on the breadboard did) or even generate sounds. I bought three smaller prototype PCBs for that exact purpose.

The first card I started working on was the graphics card. I reused the Raspberry Pi Pico from the previous solution. To avoid wasting I/O lines on the I/O chip this time, I decided to experiment with the PIO feature to hook up to the 6502 bus directly. With little documentation on the PIO back then (at least it was hard for me to find details on it) and my less skills I managed to do something. I basically made the same concept as before: two registers, one for addresses and one for data. The PIO block waited for the write strobe. If the graphics card was addressed, the block captured the data on the data bus and the single address line. This data was then saved to a variable. The main loop of the Pico program waited for the variable to update and then, based on the value, executed a command (e.g., print a character or set the cursor position). All of this was fast enough to go up to 4 MHz in the future! I left the Pico source code for that graphics card in the GitHub repository of this project.

The next one was the sound card. I searched online for sound options and found a relatively inexpensive, easy to interface (in terms of programming) sound chip - the General Instrument AY-3-8910. It's is a 3-voice programmable sound generator (PSG) designed by General Instrument (GI) in 1978, initially for use with their 16-bit CP1610 or one of the PIC1650 series of 8-bit microcomputers. It has three channels of sound with a wide frequency response that can produce almost all of the notes on an 88-key piano. These can be modified by a shared envelope generator and random noise channel that can be added to produce sound effects (Wikipedia). I ordered two of them from AliExpress. I also found out that it had a relatively simple music format if I wanted to play something that was already made. In short, there is a .ym file format, which is basically a dump of the register writes to the AY sound chip. All you have to do is write these registers from the file at a fixed rate, and you have a music player! A lot of music composed for the AY-3-8910 can be found online in this format, which is really nice. One weird thing about this chip is the way you write data to it. The data and address buses are multiplexed - first, you write the address, then the data. This is incompatible with the classic 6502 address/data bus. The solution? Use an 8255 I/O chip. One last problem is timing. To play .ym music, I had to write the registers almost perfectly 100 times per second, otherwise the music would be too fast or slow. The solution was to add a adjusted 555 timer on the card, which was connected to the 6502's IRQ line. My bus connector had the CPU IRQ exposed, so it was not a problem. I also added gating of the IRQ to enable or disable it by using a free line on the interface translation I/O chip.

I also soldered two sound chips for stereo sound, but in the end, I didn't use them. It was too much for the 6502 and not many songs in the .ym format were made in stereo.

The last card I made was an IDE disk interface card. IDE/ATA is not hard to interface because the drive acts like an Intel-style I/O device with a few registers. I already have the Intel RD/WR on the board for the onboard 8255, so reading and writing is not a problem. As for the IDE interface, one register is the data port, and the rest of the registers specify the command, status, selected address (sector), selected accessed drive (master or slave), and so on. The main issue is that the data register is 16 bits wide, while the 6502 bus is only 8 bits. I came up with the idea of using two 74574s (8-bit, 3-state D flip-flops) for the upper 8 bits of the 16-bit IDE bus. One is for reading and the other is for writing. I managed to implement access to them using only gates. I experimented with the card prototype on a breadboard before soldering it onto the card. Sadly, I don't have a schematic for it. For more information about the IDE interface, I recommend reading this article, which helped me understand it.

Software

We have the hardware, but we need something to run on it. If you're creating something from scratch, it's difficult to find existing software that will run on your machine right away. This 6502 homebrew only received two main programs: an AY-3-8910 music player and Microsoft BASIC.

AY-3-8910 Music Player

Initially testing the sound card was simple, like playing basic tones. Next, I played small .ym files by converting them into a direct AY-3-8910 register data stream and storing it in ROM. Lastly, using the IDE card that I made, I created a simple player that reads the drive sector by sector (it's difficult to implement file system drivers on 6502, so I did it without one). The sectors contain these register dumps, which are written into the AY chip. Video below shows the classic "Space Debris" track being played on my homebrew!

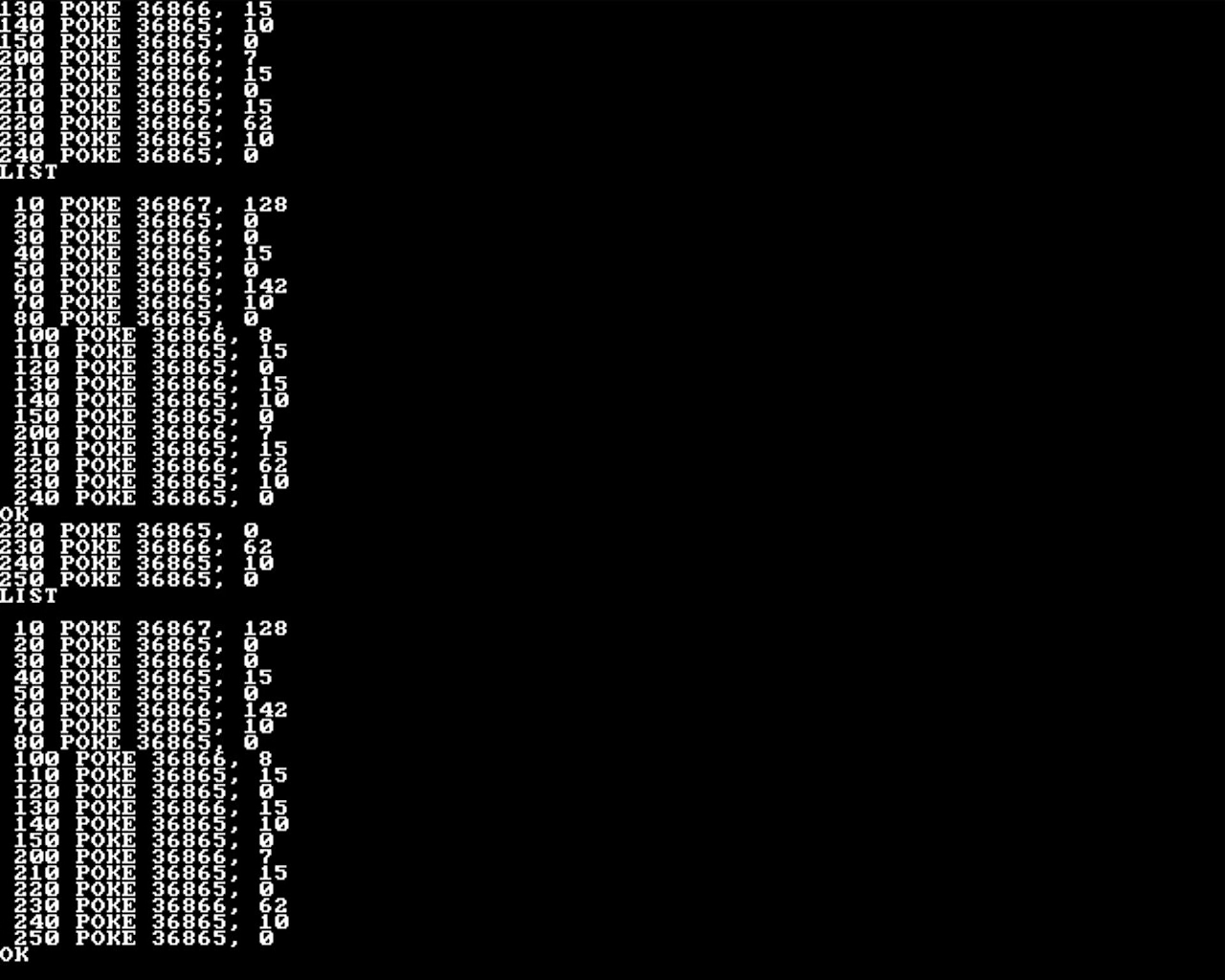

Microsoft BASIC

I think this one is more impressive. What's more classic than running BASIC on a 6502? I found this project on the internet: https://github.com/mist64/msbasic. It includes Microsoft BASIC and examples of how to port it. I remember there being two main routines that needed to be implemented: character printing and keyboard input. The first one was not very hard to implement. The graphics interface on my system is very basic - it's text mode graphics accessed by two registers implemented by the Raspberry Pi Pico. Implementing the keyboard input was harder. Actually, the keyboard controller on the prototype PCB version is the same as on the breadboard: when a key is pressed, an NMI interrupt is received and a PS/2 scan code is stored in a buffer accessible by the I/O chip. In the NMI interrupt handler, I had to read the PS/2 scan code from that buffer, decode it to an ASCII character (with shift key handling), and write the result to a circular buffer. The get character routine called by the BASIC checked the buffer and based on that, received the input. I could not find any videos showing this in action, but I found a screenshot (DVI screen capture) from when I was testing the sound card and a photo of a sample program printing on the screen.

Summary

I guess that's almost everything about this computer. For my first homebrew computer, I think it turned out great and it taught me a lot about computer architectures. Some time later, I even wrote an emulator. I have it somewhere on my computer, but for now I'm keeping it to myself. I dropped work on this computer because I had other projects to work on, but not long time later in June 2024 (the last time I worked on the 6502 was in March 2024), I managed to get pretty interesting scrap that made me go further with homebrews...

Next: Motorola 68000 Homebrew.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](http://maniek86.xyz/cmsesus/uploads/image/valid-rss-rogers.png)